By Suzanne Spellen (aka Montrose Morris)

Red Hook is one of Brooklyn’s oldest neighborhoods, with a history that is unique. With that in mind, it should come as no surprise that Coffey Street, located between the Atlantic and Erie Basins should have a unique history as well.

Here is the story of Red Hook’s early years and a well preserved row of Italianate brick houses, built for the working and middle classes, on what is now Coffey Street. The row is one of Red Hook’s most picturesque, with handsome rope details around the doors and pretty carved decorations over the windows.

Coffey Street. Photo by Susan De Vries

Red Hook’s Early Years

The street grid was mapped out when Brooklyn became a city in 1834. Most of the city would not actually be built out for another 50 years. Many of Red Hook’s proposed streets were still underwater. Coffey Street started out as Partition Street, a bulwark between inland and the waterfront, which in places was only a block away.

The Brooklyn Eagle began publishing in 1842. At that time, the land surrounding Partition Street still belonged to Matthias and Nicholas van Dyck. Various members of the Van Dyck family owned a great deal of Red Hook. Dikeman Street gets its name from them.

Partition Street was opened in 1848, along with most of the other streets in the area. The city ran public notices for contractor bidding purposes for the next several years. Roads and sidewalks needed to be graded and laid, curbs cut, and sewer, gas and water lines had to be installed.

Meanwhile, industrialists had realized what a treasure they had in what was then called South Brooklyn. The topography of the shoreline was perfect for the creation of enclosed harbors protected from the elements. Using the tons of earth excavated from the leveling of Brooklyn’s hills, they began to fill in the creeks, ponds and marshy land that fed into the sea.

A system of docks and piers was built all around and through the new harbors, creating a larger waterfront than the one across the river in Manhattan.

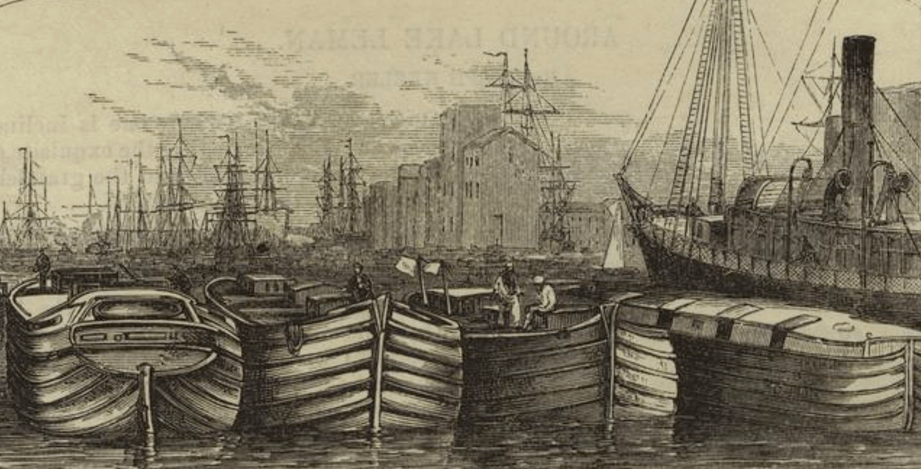

The Atlantic Basin circa 1873. Image via New York Public Library

Colonel Daniel Richard created the Atlantic Basin in 1839. It fronted Buttermilk Channel, the body of water separating Governor’s Island from Brooklyn. Twelve years later, William Beard began creating a much larger harbor, which he called the Erie Basin. It opened in the late 1860s.

Both bodies bristled with warehouses, grain storage, and heavy laden-docks full of all kinds of merchandise and materials. Manufacturing and heavy industry grew up as one moved inland, concentrated more around the Atlantic Basin, in the new neighborhoods we now call Carroll Gardens and Cobble Hill.

Red Hook’s Growth Produces a Powerful Politician

Partition Street was renamed Coffey Street in 1891 in honor of local politician Michael J. Coffey. Like the neighborhood he grew up in, Coffey was scrappy, hard-working, and tied to the sea. He was born in County Cork, Ireland, and come to the United States with his family in 1844, when he was five years old. His parents first settled in Chicago, then moved to Red Hook when he was 10.

Michael J. Coffey. Photo via Brooklyn Daily Eagle

He was a teenager when he began working in the Brooklyn Navy Yard as a carpenter. He joined the Navy during the Civil War, and served on the gunboat Monticello, where he earned the attention and respect of his captain, gaining a reputation for fearlessness and bravery. After the war, he returned to Red Hook, and settled down to a career as a contractor, building docks.

Photo by Susan De Vries

He became interested in local politics and aligned himself with Hugh McLaughlin, the powerful Democratic Party boss of Brooklyn in those years. Coffey’s district was located in Brooklyn’s 12th Ward, which covered Red Hook and its docks — some of the city’s most important real estate. A man who controlled the docks controlled a great deal of the finances of Brooklyn.

Coffey became an alderman, the equivalent of today’s City Councilperson, serving his district between 1867 to 1874, when became a State Assemblyman. He served in that position until 1892, when he once again became an alderman and president of the Board of Aldermen. In 1893, he was reelected to the NY State Senate.

Mike Coffey was a small man, only 5 feet 4 inches tall, but he cast a long shadow. His 39-year career in politics gained him the nickname “the Emperor of Red Hook,” and his district was known as Coffeyville. Before he broke with Hugh McLaughlin, he was one of the Boss’s right-hand men. Nothing went on in Red Hook that he didn’t know about, or have a hand in.

Coffey Park. Photo by Susan De Vries

He negotiated the purchase of land for Red Hook’s only city park, which was also named after him long before his death. The parkland was purchased in three parcels — the earliest and largest parcel through Coffey in 1892. Coffey Park officially opened in 1901. Subsequent parcels were purchased in 1907 and 1943, resulting in today’s park.

In 1901, he bucked McLaughlin’s Democratic establishment machine, and was accused of “treason.” He lost his seat, and went back to building docks. He developed cancer and died March 22, 1907, at Long Island College Hospital, after complications set in after surgery.

A Handsome Group of Houses on Coffey Street

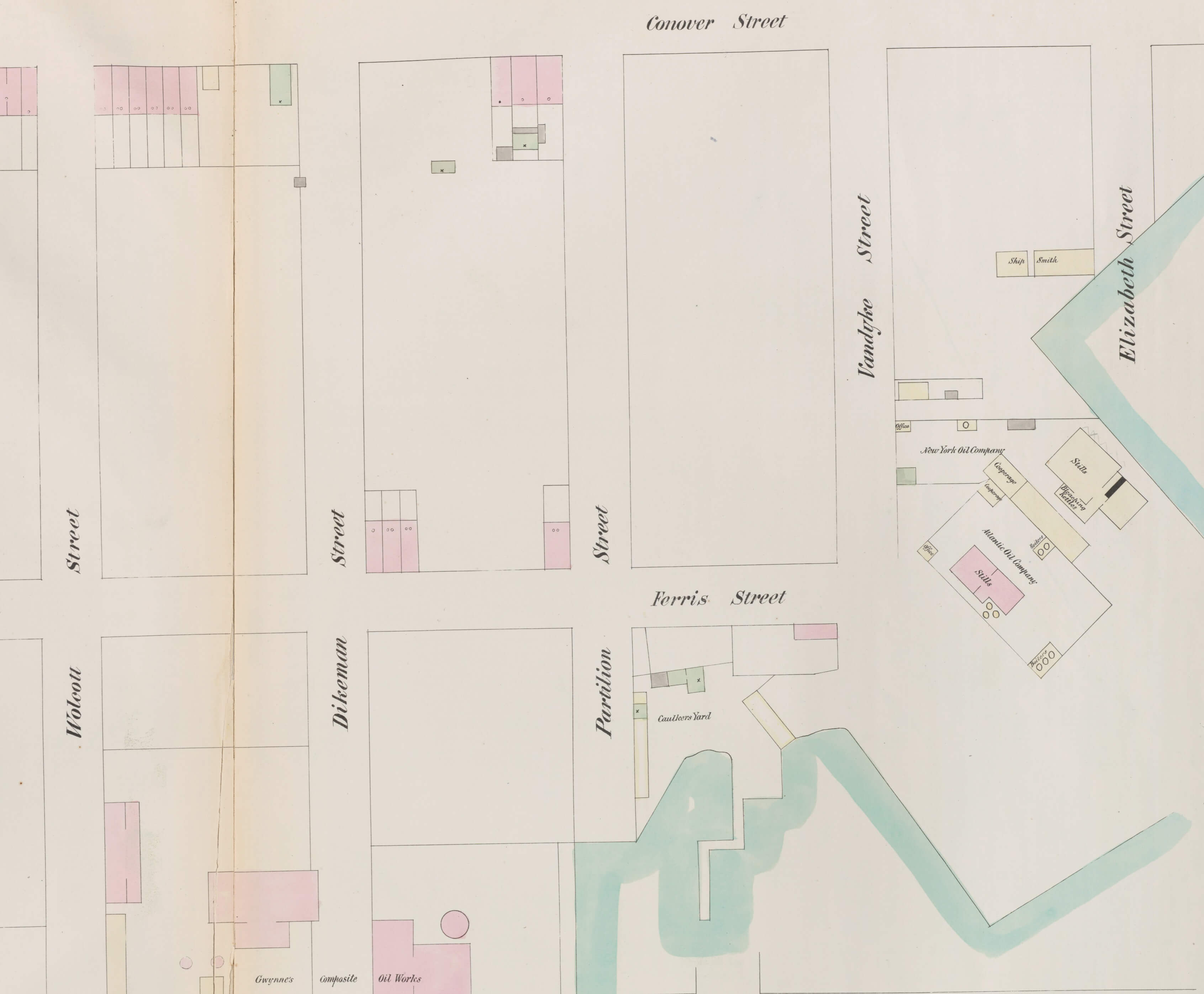

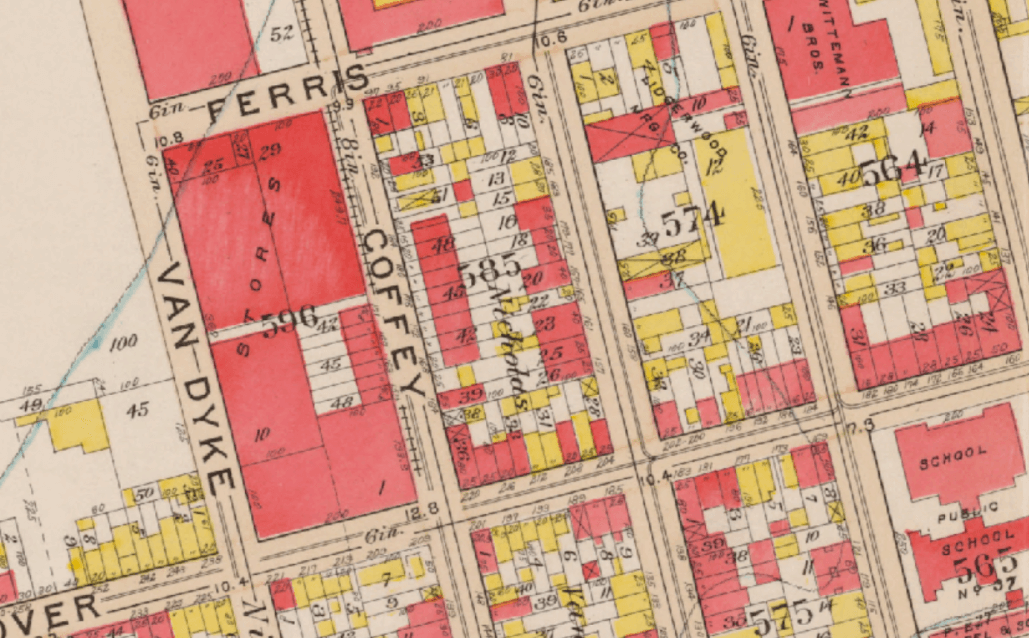

Partition Street in 1855. Map via New York Public Library

An atlas map of 1855 shows the streets laid out, but almost no buildings on Partition Street. There are a couple of row houses on nearby Ferris Street. By 1860, there are still no residential buildings.

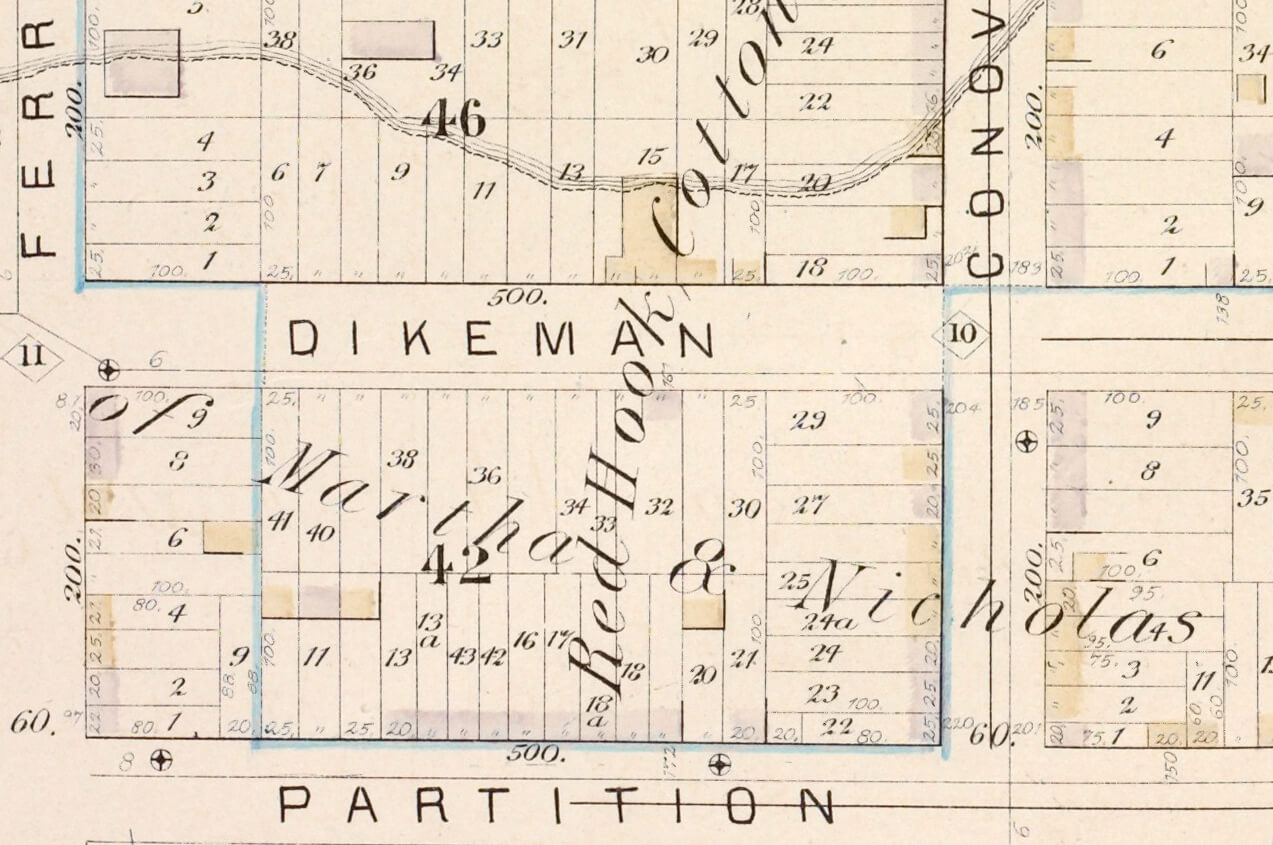

The block in 1880. Map via New York Public Library

A later map from 1880 shows these eight houses –- Nos. 168 to 182 Partition Street. The house at 174 Partition Street is mentioned in the Brooklyn Eagle in 1874. None of the others appear until the 1880s.

Photo by Susan De Vries

The houses are brick transitional Italianates, with some creativity in inexpensive ornamentation. The prominent hoods over the doors and windows, along with the floral lunettes below, add a touch of whimsy to the row. With the changes in many of Red Hook’s streets over the centuries, this remains one of the most intact rows.

180 and 178 Coffey Street. Photo by Susan De Vries

Only one house is now missing, at 174 Coffey, and most have their exterior details. Even No. 180, which had a suburban-style entrance and picture window installed, kept the hoods and lunettes. The houses also retained their substantial window sills and large arched wooden cornices, which echo the lines of the window hoods.

170 Coffey Street. Photo by Susan De Vries

The row was built by unknown builders as speculative single-family housing for middle and working class homeowners. But because of economics and scarcity of housing, all soon were divided into either rooming houses or apartments quite early on.

182 Coffey Street. Photo by Susan De Vries

Not much happened here that was newsworthy, just ordinary working people going about their lives. For most of the late 19th and 20th century, the neighborhood was solidly Irish and Italian. They rarely made the papers, except to announce funeral notices. But there were some exceptions.

The block in 1903. Map via New York Public Library

In 1903, 31-year-old John C. Steiger got himself into a lot of trouble. He was a patron at a Hamilton Avenue cigar store and pool hall when the police raided the place. Steiger made the mistake of putting his hand out to restrain Captain Patrick Summers. He was arrested and charged with interfering with a police investigation and assaulting a police officer.

178 Coffey Street

The case became much bigger when Summers and three of his men were charged with “oppression” by the pool hall owner. Apparently, they came into the establishment and threw their weight around without having a specific reason to do so. The case made the papers for several days. The outcome is unclear, however.

In 1909, a tug called the Proctor, moored on a dock nearby, sank. It was owned by James Brooks, of 182 Coffey Street. The cook, sleeping on board, was awakened by water lapping at his face. He and others escaped. It was believed the seams of the boat opened after a particularly large work load the weeks before.

In 1931, a workman named Edward Stryte, who lived at 174 Coffey, was burned while he was working in an automobile junkyard. He and his coworkers were cutting up old cars when his acetylene torch ignited the gas tank of a truck he was working on. He was knocked over and his clothing burst into flame. He was hospitalized and recovered.

Coffey Street. Photo by Susan De Vries

Today, the neighborhood championed by Michael Coffey is enjoying great popularity, in part for the “authenticity” that it retains on blocks like this. Coffeyville has been discovered.