By Suzanne Spellen (aka Montrose Morris)

The Great Depression was one of the 20th century’s most defining periods. We tend to think it started with the international stock market crash on October 29, 1929, but the industrialized world’s economies were headed for trouble several years before that. By the early 1930s, the effects were widespread in the United States. Financial institutions were failing right and left, manufacturing dropped off significantly, and all manner of business suffered.

The effects of all this trickled down from the boardrooms to the factory floor and the farmers’ fields, leaving millions of people out of work, and eventually, hundreds of thousands of people homeless and destitute.

Cities were particularly hard hit by the Depression, and New York City, with its large financial, business and manufacturing centers was especially vulnerable. By 1932, 25 percent of the nation was unemployed. Here in New York City, half the manufacturing plants closed.

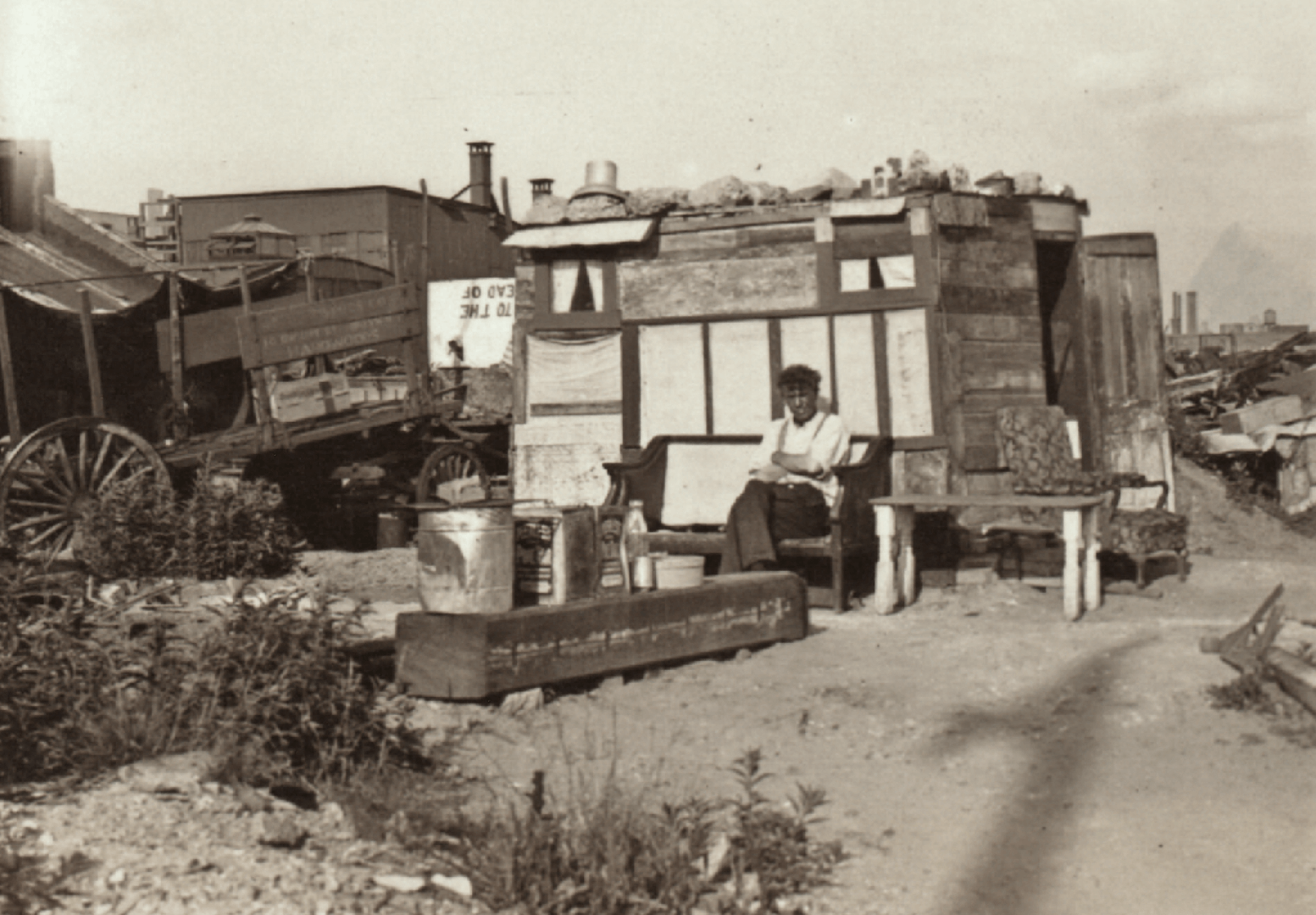

A resident of Sigourney Street in 1932. Photo by P.L. Sperr via New York Public Library

Brooklyn was especially hard hit. The borough’s industrial parks in Wallabout, Sunset Park, Dumbo, Gowanus and Red Hook were decimated, with thousands of workers laid off. That included a great many who earned their livings on the Red Hook piers.

New York was a city with an enormous and still-growing population of immigrants, many of whom held some of the lowest paying unskilled jobs and were among the first fired. Eviction would force many into the streets looking for shelter. This pattern was repeated in cities of all sizes across the nation.

Herbert Hoover had the misfortune of being president at that time. His administration and the Wall Street fat cats were seen as the cause and continuation of their plight. Evicted from their homes, desperate people built squatter’s camps on public land, creating villages that were called “Hoovervilles.”

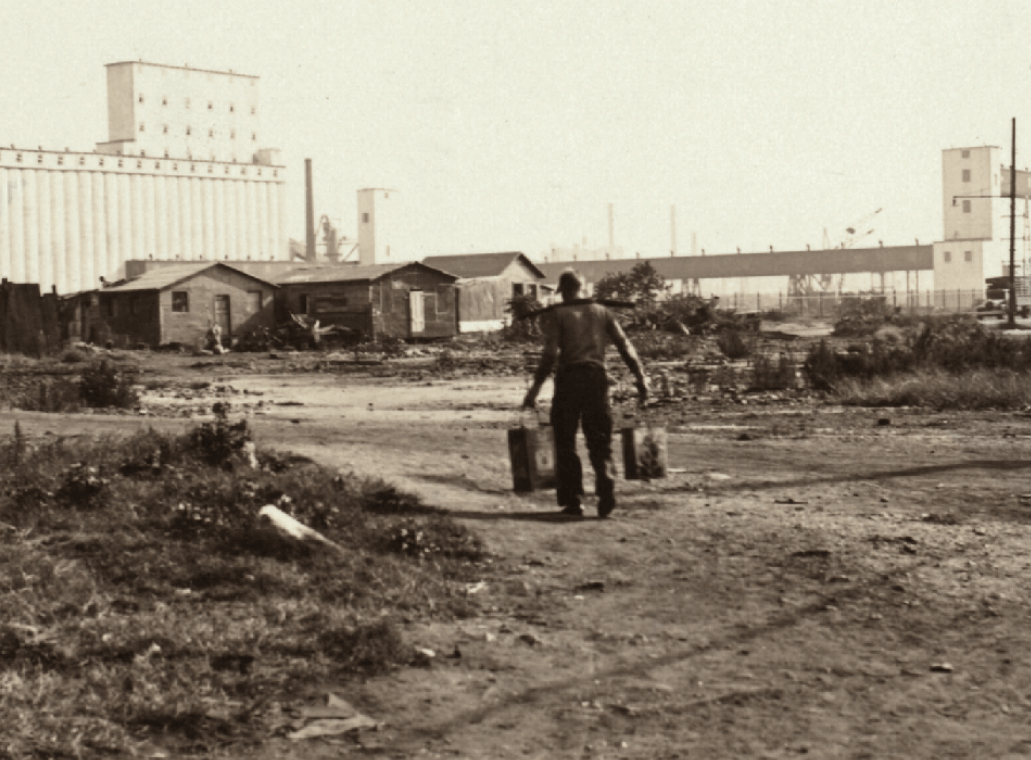

Shacks in Red Hook circa 1930 to 1932. Photo via Municipal Archives

Each borough in New York City had at least one Hooverville. Brooklyn had two or three over the course of the Depression. The Red Hook Hooverville was one of the largest. Its residents and the press called it, among other things, Tin City.

Building Tin City

No records exist as to exactly when the Hooverville encampments began in South Brooklyn. A squatter’s camp called Slab City was in existence in Red Hook in the 1880s but was torn down early in the 20th century. It was located between Hamilton Avenue and the waterfront. Some squatters remained in the area, and shacks began to appear as early as 1930. By 1932, the encampments were well established.

There were two South Brooklyn Hoovervilles – one in Red Hook, one in nearby Gowanus. The Red Hook camp was located at the base of Henry Street in the area now part of the Red Hook Recreation Center and park. It was established primarily by Scandinavian seamen who were stranded in America.

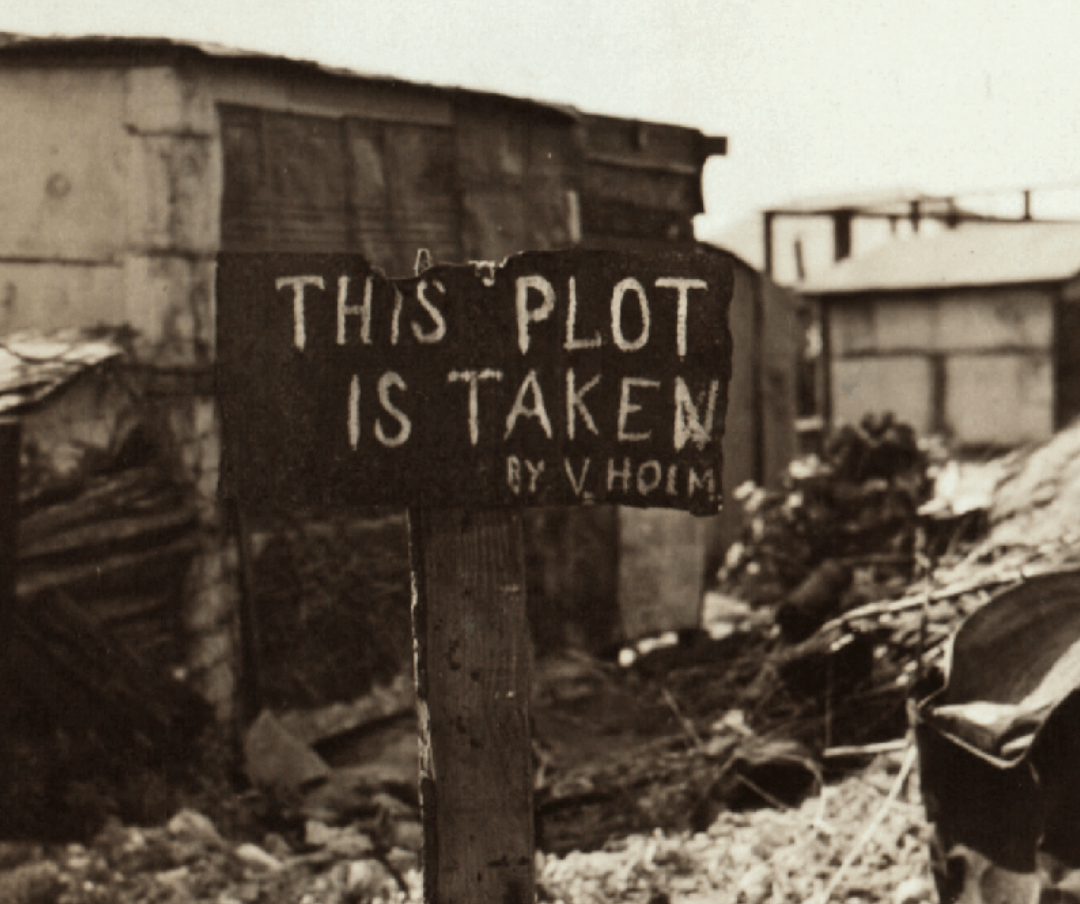

A sign in the Gowanus Hooverville in 1933. Photo by P.L. Sperr via New York Public Library

They were merchant seamen, most from Norway and Sweden, who came to Brooklyn as sailors aboard the many merchant ships that docked in Red Hook. Before the Great Depression, these men worked on the ships from Europe to America, were discharged, and were then rehired here, sometimes on different ships, for the journey home. They were primarily young and single, although a few were older and/or had wives and children here in Brooklyn.

The Depression broke that roundtrip cycle. Many ships docked in Brooklyn and fired half the crew, sailing back shorthanded because they couldn’t afford the salaries. They left hundreds of unemployed homeless sailors behind with little or no money, many not able to speak English. They wanted to stay by the docks and the hiring offices, so they camped out on a large plot of city land that Brooklyn’s city fathers had been holding fallow for a future railroad yard.

The empty lots were a dumping ground for rusted automobiles, construction waste, tin cans, garbage and industrial refuse. Using whatever they could find to build with — fencing, old buildings, roofing tin, flattened tin cans, automobile parts — the men built small shelters. Some were able to piece together small houses that resembled Scandinavian cottages, but most cobbled together whatever they could with four walls and a roof. If they were lucky, their huts had a stove of some kind and a floor, but many were as piecemeal and rudimentary as shacks of the desperately poor have been throughout history.

Living a Hard Knock Life

There was no fresh water, no sanitary facilities, little heat and little comfort. Drinking water had to be hauled in from a public pump located blocks away. Firewood was scrounged from nearby buildings and trash heaps. The men tried to grow crops, but the land was too polluted and used up and not much grew. They fished from the docks and often relied on the charity of local Scandinavian church groups and the Salvation Army for food.

In addition to Tin City, the community they created was also called Hooverville, Hoover City, Tin Can City and — most improbably, but with full irony — Prosperity City.

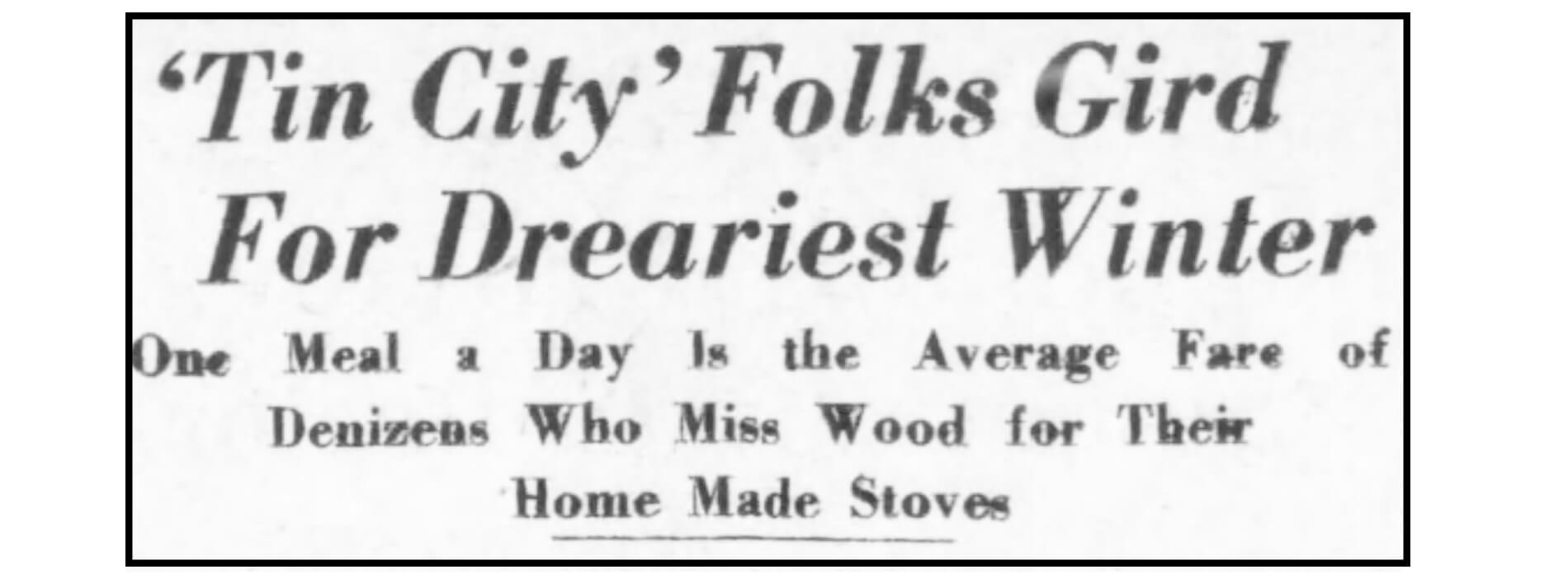

A 1932 article about living conditions in the community. Image via Brooklyn Daily Eagle

Every day the men would go to the hiring halls, trying to get merchant seamen’s jobs. They were few and far between. They would go to local businesses and homes offering to work, but in the worst of the Depression years there was little work to be found.

There was no unemployment, no Social Security, no welfare or food stamps. Those programs were all developed later, in answer to the Great Depression and the need for a social safety net. By the end of December 1932, the city estimated, there were around 200 dwellings in the Red Hook Hooverville. There were only slightly fewer next door in Gowanus.

Winters in Tin City were especially harsh. The shacks were basic shelter, not insulated dwellings. Rain, snow and the freezing winds coming off the harbor swept through homes made from whatever the residents could salvage. People filled the cracks in the walls and roofs with newspapers, rags, and flattened tin cans. They burned salvaged wood in makeshift stoves but had to be careful, as smoke and carbon monoxide could kill as fast as any fire.

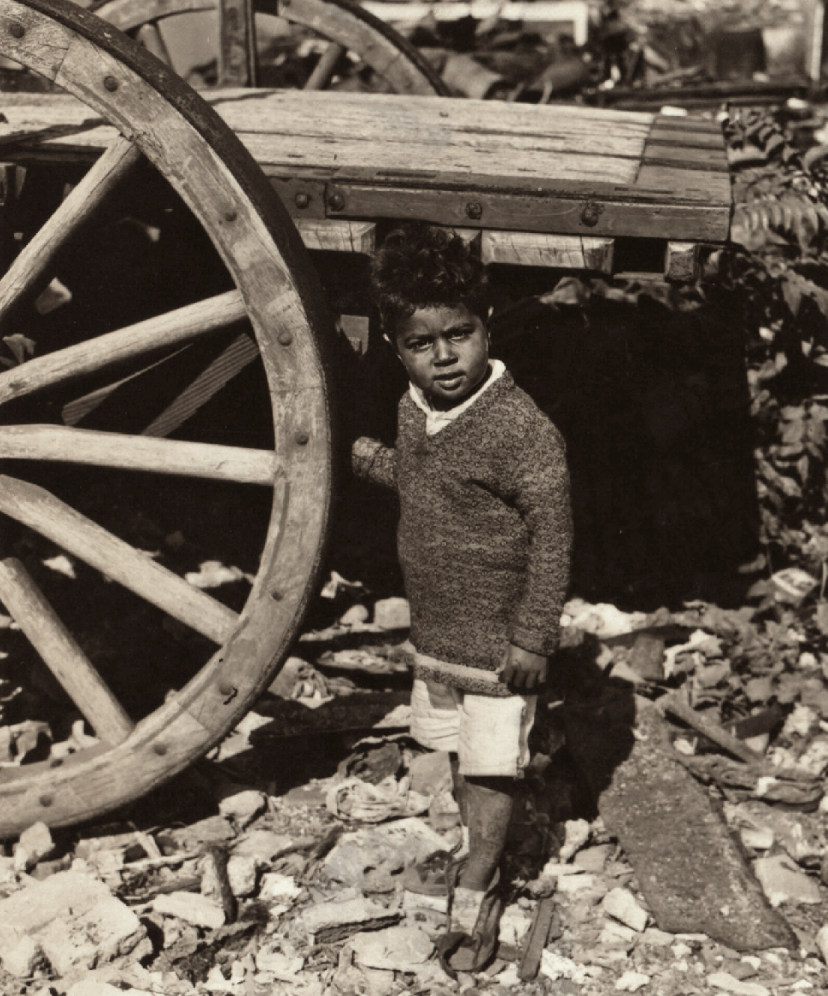

A young resident near Columbia Street in 1933. Photo by P.L. Sperr via New York Public Library

Despite the hardship, Tin City was much more orderly than one would think. There were rudimentary streets and lanes, and most of the houses were as neat and tidy as possible, some with small patches of yard around them. The people of Tin City were poor but were still proud.

There were also women and children in Tin City, although men predominated. As the Depression settled in, the community grew as Scandinavian sailors were joined by other nationalities and a lot more families. Records and photos show Irish, Hispanic and even a few black people living there. The first birth was registered on March 23, 1933 — a daughter was born to the Ramos family. An Irish midwife tended to the mother before she was taken to the charity ward at Long Island College Hospital.

Survival in Red Hook — Just Barely

Several events captured in newspaper stories tell of the life and times in Tin City. In the camp’s early days, when it was mostly occupied by unemployed sailors, bored men often turned to drink. The liquor was called “smoke” and the men addicted to it were called “smokies.” Smoke was made from painter’s alcohol — wood alcohol — which was mixed with milk and cooked in gasoline cans over an open fire. It was pure poison.

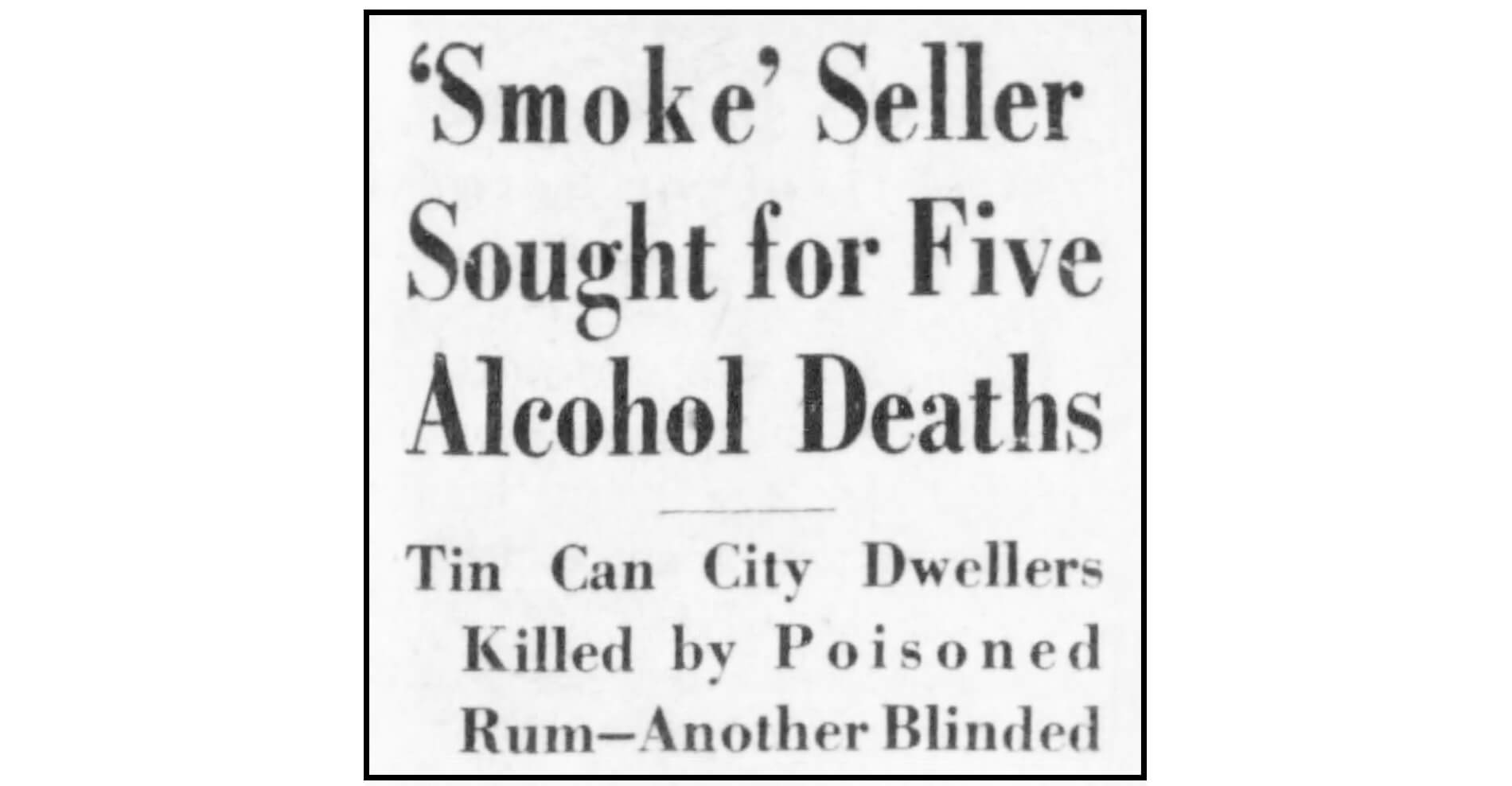

A 1932 article about the “smoke” related deaths. Images via Brooklyn Daily Eagle

On September 6, 1932, a patrolman walking his beat in Red Hook was told that men were dying in Tin City. He investigated and found several men dead, one in the street, others in their shacks. In total, five men died, and many more were seriously ill. They had all been gathered at a Labor Day party in one of the shacks and had liberally dosed themselves with smoke. Hours later, the men, all Scandinavian sailors in their late 40s, lay dead, dying or sick.

At least one of the dying men went blind before succumbing, and most of the 14 survivors also went blind. Police looked for the man who had sold them the alcohol. A salesman had visited the camp that morning and sold the men several gallons of wood alcohol at 50 cents a gallon. He told them that the substance was poison, but that the poison could be boiled off when mixed with milk. He was wrong. The salesman was never found.

By April 1933, Tin City was at its peak in population, due to the arrival of more and more families. It was estimated that more than 1,000 people lived there.

Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected president in the fall of 1932, but the Depression would get worse before it got better and his New Deal reforms began to be felt in the tin cities throughout the country.

That month, the Todd Shipyard decided to remove its wooden fence surrounding its athletic field. The shipyard offered the wood to the residents of Tin City.

Dozens of men and women rushed to the site to gather free firewood and building supplies. The desperate people couldn’t wait for the workmen to finish and they began ripping the fence apart from the bottom.

That undermined the structure, and part of it collapsed on top of them, injuring several men and women and sending them to the hospital. Those remaining continued to tear down the fence and remove it. The entire structure was gone in a matter of hours.

A resident carrying water near Columbia Street in 1933. Photo by P.L. Sperr via New York Public Library

Winter brought out the best and worst in people. The winter of 1933 was harsh. The Brooklyn Eagle published an exposé with photographs showing men using a blow torch to melt the frozen pipes of the only fresh water pump near the camp. The orderly row of houses looked sturdier than one might think, but they were buildings one might expect to see in the wilderness of the 16th century, not for people living in the 20th.

Aid was offered by city relief agencies, but often was not well planned or thought out. One agency had a small load of coal delivered to one of the houses. But when the woman of the house couldn’t pay the driver a delivery charge, he drove off with the free coal.

Many of the people doubled up in the winter to keep warm. One home had 11 people living in five small rooms. They spoke little English, had no plumbing, and when the wind blew too hard, the fire would go out. Five of the 11 were children under the age of 11. They lived on the eight dollars a week given to them by the city’s poverty relief program.

The End of Tin City

The deaths of the sailors from poisoned liquor in 1932 put Tin City on the city administration’s radar. More than one city official wanted to have the entire camp emptied and torn down as soon as possible. The city’s Hoovervilles were embarrassing to the city on many levels. By 1933, the area was being considered for new federally funded housing, a project that would eventually become the Red Hook Houses. But Robert Moses also had his eye on the area, which he wanted for a public park.

A shack near Columbia Street in 1933. Photo by P.L. Sperr via New York Public Library

Slowly, people began moving out of Tin City. Families became eligible for the new WPA-sponsored housing. The New Deal began to deliver on its jobs programs as well. But it would take a couple of years for everyone to leave. In 1934, powerful Robert Moses got his wish. The Red Hook Houses were shifted a few blocks away, while Tin City was planned as playing fields in the new Red Hook Recreation Center and Park.

The property was slated for total evacuation by September 1, 1934, but advocates for the residents petitioned the city for an extension. There just wasn’t enough time to find housing for the displaced. It was suggested that many of Tin City’s residents could be paid to tear it down, giving them employment and money to get them through the winter. It is unclear if that became a policy, but no doubt many were hired to do just that.

The pool soon after completion in 1936. Photo via NYC Department of Parks & Recreation Archives

Excavations for the pool began in October 1934. The Red Hook Recreation Center, including the pool and bath house, opened to the public in August of 1936. The playing fields, once home to 1,000 people, opened in 1940. South Brooklyn’s Tin Cities, the Hoovervilles, became storied memories, all but forgotten as World War II jumpstarted the national economy, opening factories and piers once again, and sending more than a few of South Brooklyn’s eligible young men to war, and their parents back to work. Today, only black and white photos, the ones seen here, remain.

Red Hook Park in 2017. Photo by Susan De Vries